Seminar on regenerative agriculture held for local farmers

Advertisement

The Seine Rat Roseau Watershed District held a regenerative agriculture seminar on Feb. 6 where farmers were informed about the benefits of this form of food production.

“We’re using agriculture practices that are working with nature,” said Virginia Janzen, regenerative agriculture program coordinator with the SRRWD. “So, we’ve seen that improved soil health: so the structure of the soil, what’s living in the soil, the different cycles of the soil.

“As the watershed (district) we’re really interested in observing and learning about how regenerative agriculture practices helps with water infiltration. So, keeping the water going down the soil profile rather than running off and then carrying nutrients and soil with it into our streams and rivers.”

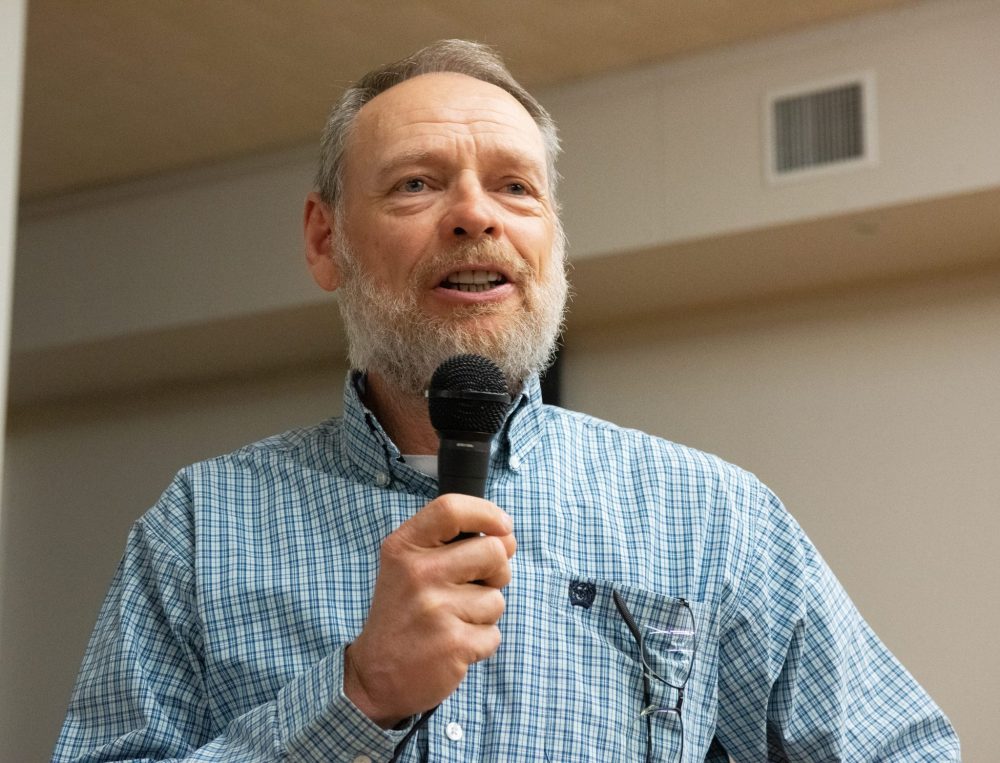

The keynote speaker was Garry Richards who runs a cattle farm in Bangor, Saskatchewan. He’s been farming since 2000 and practicing regenerative agriculture since 2003.

“Every time we have to fight nature we usually have to work harder, spend more money, and assume more risk,” he said.

“The philosophy is to take free inputs – solar energy and rain – and convert them into a marketable commodity. So, for us that’s forage and beef.”

On his 6,000-acre farm he has planted a mix of native grasses including cover crops of sweet clover, alfalfa, red clover, rye grass, oats, barley, and sunflowers. The land is grazed by 1,000 cows and calves.

He increased the organic matter in his soil by one percent over five years and stopped overland flooding through regenerative agriculture.

“The most difficult thing to do is to change the way you think. It’s the mind shift. The most difficult thing is to change the way you see things. Change your perspective. It’s that change thing it’s hard for humans to do,” said Richards.

“As far as implementing it, as long as you have the goal and knowledge, there’s lots of us that have done this. They’re sitting right in this room and understanding those principles. It’s not rocket science. So, the biggest thing is to just change the way we think and it’s our thinking perspective that’s the biggest challenge.”

Darnell Plett only started his mixed farm 14 years ago and he has implemented some regenerative agricultural practices. He practices low tillage on his 700-acre farm between Lorette and Grand Pointe. The SRRWD has sponsored him to buy compost to spread over his fields and he makes a slurry of worm castings and water which he sprays over his seeds as fertilizer and to help the bacteria in the soil flourish.

“It’s like taking probiotic pills for your gut,” he said.

Plett notes he hasn’t used fungicide or insecticide seed treatments on his soybean or wheat seeds for about 10 years.

“You put the neonicotinoids on there and stuff and I don’t think you need to, and my yields are very good. It’s a different way of looking at it. Being a beekeeper also makes me more aware of some of these dynamics having healthy insects instead of killing everything.”

Plett said one of the problems he has with the seminar is that it largely focuses on regenerative agriculture for producers of livestock and he mainly produces cash crops.

“I glean what I can, but a lot of it hinges on the livestock, so I’m a bit stuck there,” he said.

Janzen said the SRRWD is still learning what crop farmers like Plett can do to have a regenerative agricultural farm as there are major hurdles, such as a short growing season which makes it harder for a shoulder season of cover crops.

“So, farmers right now are still experimenting on their farms with how they can incorporate regenerative agriculture practices. So, that might mean that in the future (they’re) intercropping with cash crops or that might mean developing relationship with a livestock producer and incorporating livestock on their farms with that relationship,” she said.

While it’s not difficult to implement regenerative agricultural practices, results are not seen for a few years but the rewards are great, according to those in attendance. So, the question that comes to mind is why aren’t more farmers doing it?

“There’s very little public support for it,” said Gary Martens, a retired farmer who now has 24 acres in Kleefeld where he practices mixed farming.

Since companies who make fertilizer, pesticides, herbicides, and other farm suppliers make very little money off of regenerative agricultural farms, they are less likely to support them, according to Martens.

“We can’t look to politicians to help us. Because this kind of agriculture is on a fringe and they’re not going to support that. It has to be widely accepted before they will.”

Martens’ advice for farmers who are considering regenerative agriculture is to look at the profits.

“I don’t think we have to convince farmers about the principles of this when they see its more profitable than what they’re doing.”