Ojibwa oral tradition explores Mennonite history

Advertisement

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/11/2024 (220 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Mennonites who study history are well-versed on their arrival to Manitoba 150 years ago. The stories of their hardships and success on the land have been well documented.

But their interactions with the people who already inhabited this land before they arrived are not recorded in books, at least until now.

The Secret Treaty, a story handed down through generations of Ojibwa people, is one of those stories.

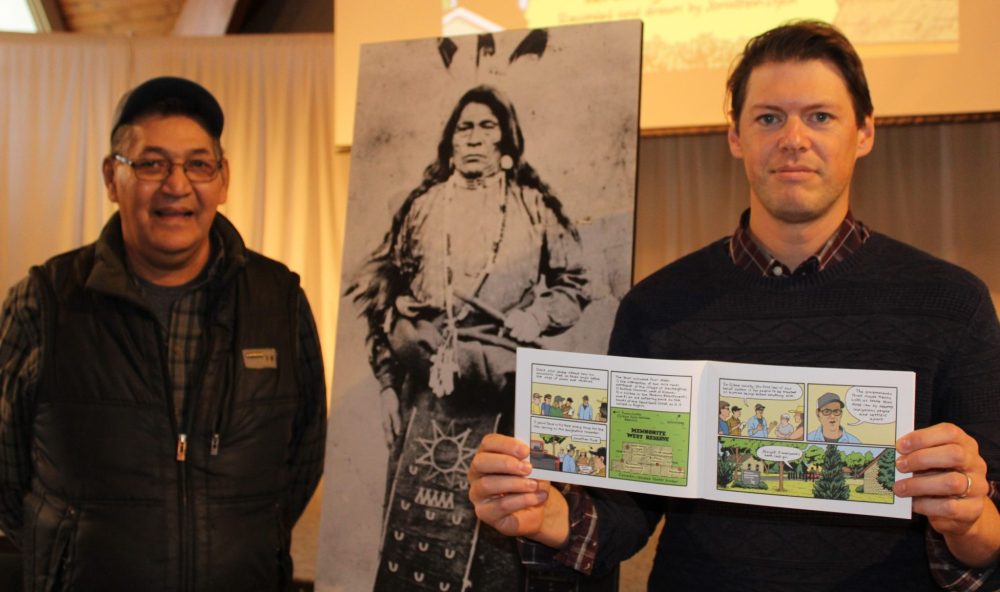

Told by Dave Scott, a Swan Lake First Nation man who’s spent his life preserving the oral traditions, The Secret Treaty is a graphic novel recorded and illustrated by Jonathan Dyck that explores just one of those early stories.

Scott and Dyck presented their book to a group at the Mennonite Heritage Village on Sunday.

It tells the tale of the first meetings of Mennonites in the Altona area with the Ojibwa and the secret treaty that followed.

Scott said the idea for the book came after a conversation he had with Will Braun, editor of the Canadian Mennonite Magazine.

Scott shared the story with Braun who had never heard it.

“I thought why haven’t they?” Scott said.

There was some awareness in the Mennonite community, Scott said. He talked to a resident who lived near Swan Lake First Nation and asked him if he had heard of the secret treaty.

“He said, ‘Oh yes, but we don’t talk about that,’” Scott said. “I’ve been trying to get these stories out for years and years, but nobody would listen.”

The secret treaty between the Mennonites and Ojibwa was established thanks to Ojibwa leader Big Goose.

During the first meeting Chief Big Goose had to convince the Mennonites they meant no harm, and in turn they learned that the Mennonites were pacifists.

That allowed for a handshake treaty that was about maintaining peace, sharing knowledge and mutual support in times of need.

“We knew something was coming at us, but we weren’t sure what it was,” Scott said of the time of increased settlement.

But the treaty remained a secret.

“It’s secret because Western societies or white people couldn’t talk to Indian people,” he said. “Only the federal crown could talk to ‘Indians.’”

The old Ojibwa language had a word for Mennonites.

Originally all of the German speaking settlers were called mee-shee-doon, which translates to the bearded ones. That word is still used today to describe Hutterites.

Later Mennonites were known as “the persecuted ones” instead.

Scott said peace was preferable to the Ojibwa whose first law in their belief system is to treat all people as human beings.

But as the book explains, that view wasn’t shared by all. An Ojibwa warrior named Blue Cloud came to Manitoba with stories of how the U.S. army mistreated Indigenous people. He encouraged local Ojibwa to start killing off the white settler population.

Blue Cloud was killed by Big Goose in what is now the Grassy Lake area to stop those beliefs.

The secret treaty was not destined to last.

The book explained that Whip-poor-will, an Ojibwa leader from Roseau River saw that the Mennonites received the land they were promised, but his people had not.

They expected the Mennonites to intercede on their behalf with the Indian agent, but there was no support, and hand-shake treaties became a thing of the past.

Scott said using the format of a graphic novel, suited the story telling and also captures the imagination of children who read it.

“They look at it, they read it, and they ask questions from it,” he said. “That was the intent, to capture the young people, the kids’ imaginations.”

Scott said stories like these have also attracted interest in non-Mennonite community. He’s fielded questions from people in Homewood, St Claude and Baldur from people curious of their ancestors’ interactions with the original inhabitants of the land.

For Scott this has been a labour of love.

Swan Lake First Nation began collecting stories from their elders in 1971. At the age of 16, in 1976 Scott took over that responsibility. Other work was done thanks to people like Marie Gordon who recorded the elders. Those recordings are still used today by Scott who’s first language was Ojibwa.

Proceeds from the telling of these stories go to the cultural centre at Swan Lake.

“These are not my stories,” he said. “All those stories are community stories. They don’t belong to me.”

The responsibility of recording and retaining the stories is not a heavy burden for Scott who said he enjoys the work.

“I’m so honoured they entrusted me with that responsibility,” he said. “It’s such a fascinating thing to be able to know those stories.”

Illustrator Jonathan Dyck grew up in the Winkler area and he said he was interested in learning more about the Mennonites arrival.

“I knew that our accounts of our history were not sufficient,” he said. “Not only was this history incomplete, it tended to be fairly self invested, a story of suffering, hardship and eventual triumph.”

Dyck said the graphic novel approach to telling the story seemed to work.

“The experience of hearing oral history is very different than reading a book,” he said. “So, I kind of wanted to do something that’s a little different and I think it fits nicely.”

For Scott, he hopes the book is another small step in creating a better future.

“My hope is one day my grandkids will meet your grandkids, and they will hold their heads high, and they will shake hands and go for a cup of coffee,” he said. “I hope that I can share more of these stories with you over time.”