COLUMN: Village News – Mennonite reflections

Advertisement

The exhibit “Mennonite Reflections: Arriving in Manitoba 150 Years Ago” is currently featured in the Gerhard Ens Gallery at Mennonite Heritage Village. This article is the third in a series highlighting each of the seven themes presented in this exhibit.

Theme 3 – Passage Across the Globe

Mass migration across about 20,000 kilometres of land and sea was, until the 1870s, a daunting proposition, given the time, expense and logistics involved. What changed is that exactly in time for the 1874 emigration, new railway connections, steamships, and paddle-wheelers reduced travel time from many months to just six to seven weeks, and walking to just the last five miles from the Red River to the immigration sheds.

The route was broken into three parts, the first from home village in South Russia (Ukraine) to Hamburg in Germany in six different trains, and then from Hamburg via Hull and Liverpool to Quebec by ocean steamer, and finally from Quebec to Winnipeg by various trains and boats. The financial burden was staggering, costing about $50 per adult fare, with reduced fare only for children under eight. So, for example, a family of parents, two teenagers and one child would pay about $220 or more depending on the amount of freight they had, plus the substantial cost of a passport. In the mid 1870s, $220 was the equivalent of two years’ wages for a day-labourer in South Russia, or one year’s wages in the USA, and the equivalent value of a newer house-barn in Steinbach in the later 1870s. An additional complication was that the sale of property in Russia was delayed and, for one Bergthal village, most of the proceeds from the sale were never forwarded to Manitoba. Ontario Mennonites quickly collected about $20,000 to help indigent immigrants and then secured a $100,000 loan from the government, using their property as collateral. This money was then distributed locally as needed to create a further debt, known as the Brotschuld (literally “bread debt”). This amount was finally paid back by the early 1890s, with some forgiveness of interest.

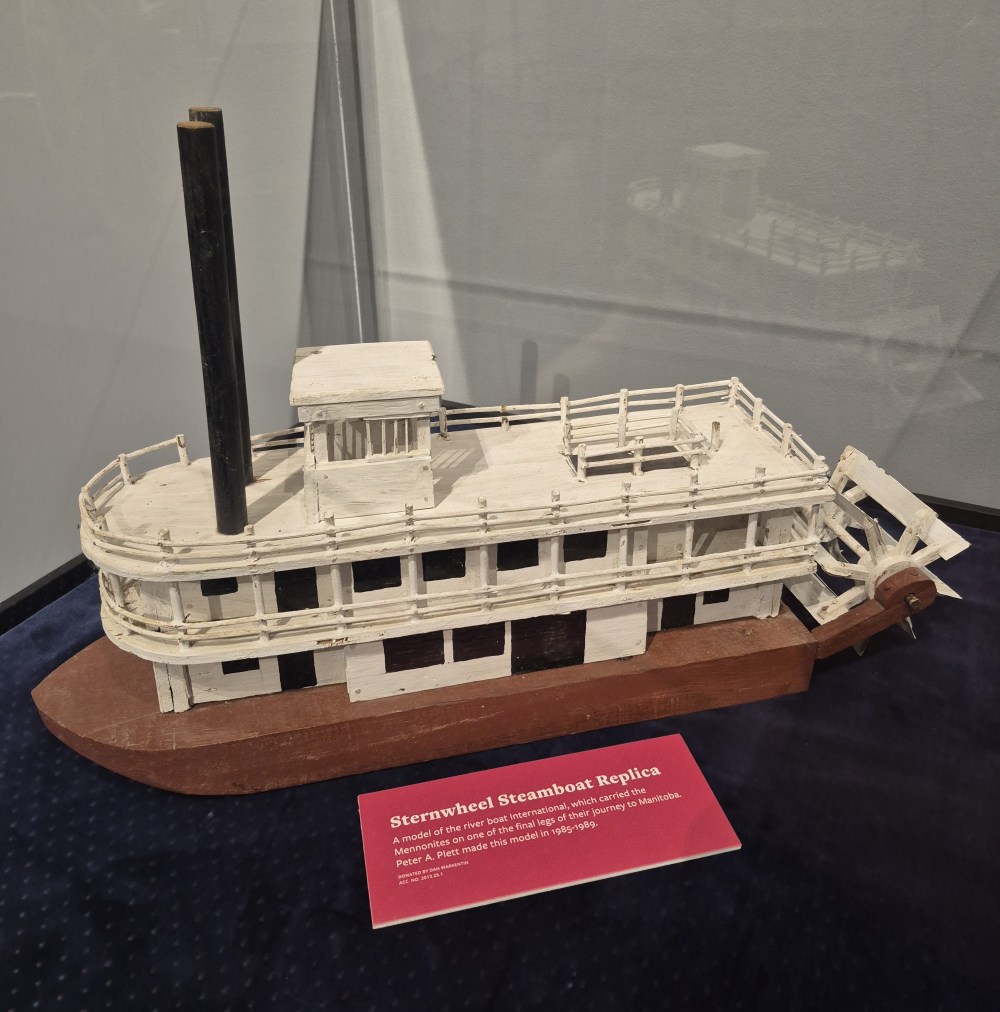

Nor was the voyage itself without its problems. American railway agents tried to entice eastern European emigrants to move to the USA while special Canadian immigration agents in Germany tried to counter the propaganda. In the end, about one third of the Mennonites chose Canada. In the confusion, the first Mennonites bound for Canada ended up taking the wrong steamship line and landed in Quebec to find they had no passage to Winnipeg. Fortunately, the government quickly decided the special passage warrants promised in the Lowe Letter would be honoured with any shipping line. A second complication arose in Toronto where the Mennonites discovered that they were to use the all-Canadian Dawson Route. This route led from Thunder Bay to the Northwest Angle Inlet via a network of rivers and portages, and from there by Red River cart the rest of the way to Winnipeg, an additional 4-week journey involving about 25 transfers of freight and passengers. J. Y. Shantz persuaded the government to allow the Mennonites to travel via Duluth to Moorhead by train and then by riverboat to Winnipeg for an extra $2 per fare with a travel time of only four days. Apart from the cost to each Mennonite, the government estimated that direct subsidies per fare were $20 above the additional indirect costs for overhead.

The most devastating part of the trip was the death of infants, women in childbirth, and the elderly, some lowered into the ocean with a short ceremony, and others given to strangers enroute when time did not allow for a burial. Over three years, almost every border crossing or train station saw at least one child quickly handed over for burial in an unmarked grave. Upon arrival at the Shantz immigrations sheds, more children died and were buried on a rise a short distance from the sheds.

The passage from Mennonite village in Imperial Russia to the newly created Province of Manitoba was a monumental odyssey of faith, beginning with the loss of everything familiar and the crippling cost of property divestiture, then an arduous journey with the traumatic deaths of loved ones, and ending with disappointment upon first arrival on the reserved land.

The next article in the exhibit series will focus on the Mennonites’ arrival in Manitoba, beginning in 1874.

Don’t miss this exhibit at MHV!

Ernest N. Braun, Niverville, is a retired high school teacher with an interest in Mennonite history, an interest that has prompted various involvements including editing the Historical Atlas of the East Reserve, consulting for the new video Where the Cottonwoods Grow, and working with the team that created the “Mennonite Reflections: Arriving in Manitoba 150 Years Ago” exhibit at MHV.

Upcoming events

Feb. 1 from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. – Winter in the Village. Visit the village and enjoy the light displays, kick sleds, skating, snowshoeing and more. Winter admission rates apply. Visit www.mhv.ca for more details.

Feb. 2 – 7 p.m. Vespers Service.

Feb. 15 and 16 – Winter Carnival – A community winter event, with music, games, activities and food for everyone.